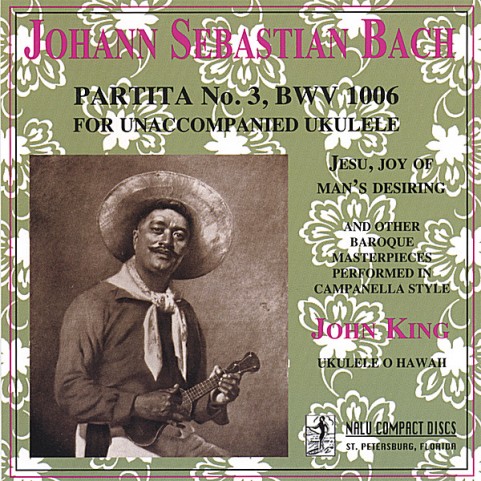

John King pioneered classical ukulele with his performances, recordings and arrangements of works by composers including Bach, Mozart and Beethoven. A defining moment in his ukulele journey was the discovery of campanella. Writing about his CD of Bach arrangements on the Nalu Music blog King had this to say about campanella:

“I began experimenting with arranging classical pieces for the ukulele about 1985 and soon realized the baroque guitar technique known as campanella was eminently adaptable to the ukulele’s my-dog-has-fleas, re-entrant tuning. Campanella, which means “little bells,” is a way of playing successive notes on different strings to create a harp-like sound. The result of all my fooling around is this CD.”

The release, in 2001, of King’s CD Johann Sebastian Bach for Unaccompanied Ukulele proved that in a master’s hands the ukulele could be a sophisticated, classical instrument. In spite of his use of the term classical ukulele King’s arrangements were diverse. They included folk tunes such as Danny Boy and Greensleeves and Hawaiian songs such as Aloha Oe and Ka Ipo Lei Mano.

The publication by Flea Market Music in 2004 of John King’s The Classical Ukulele offered ukulele players a new and exciting challenge. The gauntlet had been thrown down. I’m sure John King would smile to know that The Classical Ukulele continues to be a best seller today and one which has inspired a new generation of classical ukulele players, including myself. John King is the main inspiration behind my classical ukulele journey. We share a similar background in classical guitar and a mutual love for the humble soprano tuned high g C E A. John King is, and will always be, the King of Classical Ukulele!

In this blog I’d like to take a closer look at playing campanella style on the ukulele. I often receive emails asking me about campanella. Although it is a very popular style there are still a lot of myths and misconceptions about campanella. Campanella is possibly the most complex way of playing the ukulele. King was absolutely spot on when he said, this stuff is really hard to play! That’s because it is counterintuitive and can really mess with your head. Campanella passages are technically demanding for both hands and the irregular positioning of the notes is often in conflict with what your ear is telling you to do.

In campanella arrangements the notes are always placed on a different string. Pieces often utilise the full length of the fingerboard and incorporate big stretches and sudden leaps in position. The more compact soprano scale is, arguably, more suited to this style of playing.

Here’s me playing the Hag With the Money (if only) in campanella style!

The beauty of campanella can only be fully appreciated if the notes are allowed to ring on and over each other to create the desired harp-like effect. Left hand notes have to be held for as long as is physically possible and the strings need to be allowed to vibrate freely. This means that planting the right hand fingers, a technique which is often done in classical guitar, is not an option as this would dampen the string and stop the sound. Campanella is a very precise art which requires great attention to detail.

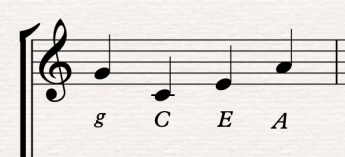

The first thing for us to consider is the re-entrant tuning of the ukulele.

Compare this to the linear or low G tuning.

Even if you don’t read the notation you can still see the more logical ascending pattern of the linear tuning. From 4th to 1st string the notes are rising 4 steps (perfect 4th); rising 3 steps (major 3rd) and rising 4 steps (perfect 4th).

On the other hand the pattern for re-entrant tuning is: falling 5 steps (perfect 5th); rising 3 steps (major 3rd) and rising 4 steps (perfect 4th).

With re-entrant tuning the 4th string is the 2nd highest string.

Why does the tuning matter?

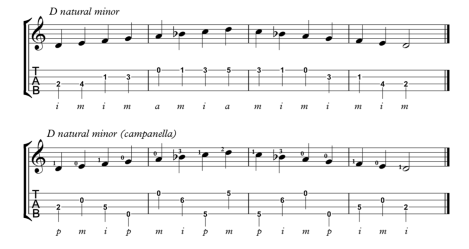

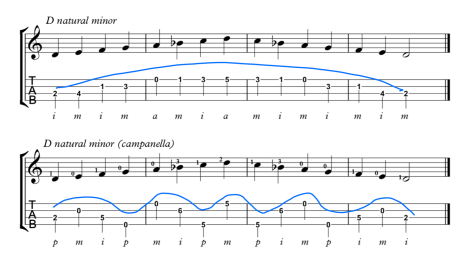

The best way to demonstrate the impact of the tuning is to look at a scale played in a linear fashion and then played in campanella style. I’ve chosen the D natural minor scale (or aeolian mode). The notes are exactly the same in examples 1 and 2.

The difference between example 1 and example 2 can be seen in the tab. In Ex.2 the notes are placed across the strings. If you cast your eye over example 1 you can see how the notes rise and fall creating a curved line which mirrors the notation.

In the campanella version the notes are dotted across the strings in what appears to be a haphazard way. This creates a wave effect rather than a curved line. (Sorry about my dodgy drawing!)

Just to reiterate: in both examples the notes are exactly the same, it is the placement of the notes on the strings that is different. The wavy versus arched line is a visual representation of what we are trying to capture i.e. waves of sound as opposed to one long rising and falling curve.

Tab is essential in campanella pieces as it clearly indicates where the notes are placed. I often feel as if the tab is speaking to me because it also gives a visual indication of the effect the composer/arranger wants us, the player, to create.

If you use low G tuning the campanella effect is compromised because all the notes on the 4th string have to be placed on other strings. Thus, reducing the effectiveness of the campanella. The scale is also less practical to play.

Ring those Bells!

What we are aiming to achieve in campanella playing is maximum over-ringing. This means that each note has to ring on for as long as possible. Of course the ukulele has such a short reverberation time we are really demanding a lot. To achieve the over-ringing careful consideration needs to be given to the left hand fingering.

For example:

In the D minor scale (see the campanella version in insert below) there are 2 considerations for the shift from 2nd position (2nd fret) to 5th position (5th fret).

Option 1. The 1st note (D) is played with the 1st finger. The 1st finger then slides up to 5th position while playing the open 2nd string (E). This works but does does it allow enough over-ringing between the D and the E?

Option 2. The 1st note (D) is played with the 1st finger. 1st finger stays in 2nd position (ie keep holding down the D with 1) while the open E is played. The 3rd note (F or 5th fret 3rd string) is then played with the 4th finger (pinky). The D should be held down until the F is played.

In version 2 a little more over-ringing is achieved between the D and E. But there is still the problem of when to shift up to 5th position and, consequently, that shift will stop the D. It will also impact on the amount of over-ringing we can squeeze out of the F. In order to determine that we need to look at the next notes in the scale.

The 4th and 5th notes of the scale, or G and A, are played as open strings. This allows plenty of time for the left hand to move up the fingerboard. The consideration is when to release the 3rd note of the scale (F on the 5th fret 3rd string). As soon as you release the F it will stop sounding and, thus, stop the over-ringing effect. And the over-ringing of the E, F & G is really very nice! I practised this move a few times by keeping the 4th finger planted for as long as possible and making the shift as I played the open A. At this point the 3rd finger moves to the Bb (6th fret 2nd string). When played at speed the sudden leap up the fingerboard meant the 4th finger had a tendency to sound the 3rd string as it released the string thus creating an undesirable hint of C. Played slowly the release was more controlled and consequently less likely to create the extra C sound. But the shift was still ungainly.

Playing the scale at a fast tempo I preferred to use method 1 as it felt more secure and fluid. I didn’t think that shortening the over-ringing between the 1st (D) and 2nd (E) notes was that noticeable.

Moving on:

Now the 3rd finger is on the Bb (6th fret 2nd string) keep it planted. Finger 1 goes to the C (5th fret 4th string) and finger 2 plays the D (5th fret 1st string). Notice how the notes A, Bb and C are ascending in the notation but visually descending in the tab. This feels very counterintuitive! Perhaps it’s my guitar brain but as the pitch rises I am used to physically moving up the strings and/or the fingerboard. These 3 notes played as a campanella, however, are turned upside down.

Fingers 1, 2 and 3 stay planted on their respective strings until they need to be released for the open notes.

We have the same dilemma with the F (5th fret 3rd string) in the last bar – do we use 1 and slide back to D? Or do we use the pinky and release slightly earlier? It’s up to you. Both work and if this were a melody the final choice would depend on the tempo, the mood of the piece, how much control you have over your pinky and the effect you are trying to evoke. In other words the considerations are both musical and technical.

Tut Tut!

Someone recently chided me for not obeying the note values in my campanella scale exercises. In other words I was holding the crotchets for longer than their technical sound duration. But this, of course, is the very nature of campanella! Notes are held for as long as possible, or as long as desirable. If we notated their correct values (and this could only be estimated) the score would look very complex with multiple overlapping voices. We would also have to become very scientific about how long each note should and could ring on. The music would lose some of its mystery and spontaneity.

Campanella versus Arpeggios

Campanellas and arpeggios are often confused. They are, however, two different techniques. A melody can be arranged in campanella style. A chord can be played as an arpeggio. An arpeggio is a broken chord. In other words a chord, rather than being strummed or played as a block of sound, is played as a succession of notes. In the example below the C major chord is shown 1st as a block chord and then as a series of possible arpeggios. The notes of the C major chord are C + E + G, or 1st + 3rd + 5th degrees of the scale. The arpeggio utilises these notes but played in a variety of ways.

C Major Scale in Campanella Style

Here’s a video on playing the the C major scale in campanella style with a series of exercises. You can download the PDF by clicking the link below:

c major campanella scale exercises

Here’s me playing Bonnie Dundee from my 35 Scottish Folk Tunes for Ukulele published by Schott. This arrangement incorporates both campanella style and some chords.

If you like campanella you might also like to check out the work of Jonathan Lewis. This is his website: Jon’s Ukulele

Sounds as though the style could be tricky…but worth a try.

LikeLike

Yes, it’s tricky Sylvia and needs slow and careful practise but is worth the effort. Thinking of continuing the campanella theme with another tutorial on an easy piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That would be great. I have just looked up Your C Major Scale Exercise and will look at that and the examples that you have given above.

LikeLike

I love your playing, Sam, and Campanella style has opened the ukulele up to me in a whole new way.

I understand the benefits of the small size of the soprano’s fretboard, and I imagine Campanella style can be played on any high-g ukulele. That said, if I wanted to maximize the bell-like ringing of Campanella style, are there other qualities I ought to look for when purchasing a ukulele? Wood choice? Another way of asking is, what makes a good ukulele?

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can play campanella on any size ukulele. What makes a good ukulele is a big topic. Solid top is essential. Wood is also factor but it’s the quality of the build that makes the difference. Price is a guide. If you go to a ukulele shop and try out a range of ukes you will hear the differences. It’s also worth looking at reputable uke makers and considering a hand made uke.

LikeLike

Hi Sam, your tutorials are so helpful and well written – Thank you .I am just starting to learn some simple campanella pieces and the challenge is so worth the reward. I have to laugh at myself sometimes though as I have fingers planted all over the fret board and when I go to lift one invariably the wrong one lifts. This leads to me staring like a madman at the finger that needs to lift when I play the piece again 🙂

LikeLike

Great post and thanks for the shoutout! In discussions about high G versus low G I’ve seen teachers on the net saying things like low-G is good for fingerstyle while high-G is better for strumming. Hmmm, guess they’ve never heard of John King! One one of these days I’m gonna put a low G on one of my ukes, but up till now I’ve always thought that it would be just like a guitar with two strings missing…

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for this blog, I have been slowly working my way through the Sor, 21 Progressive Lessons and enjoying the melodies. Your discussion of Campanella style has reminded me to hold the appropriate notes whenever I can. It has made these pieces even more satisfying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Judy! Yes, they do work nicely on the ukulele. That’s reminded me to play these again!

LikeLike

Hi Samantha, I just have to tell you how much I appreciate your blog, your music and your tutorials! Thank you for all your efforts that show your deep love for music and spread the word of the ukulele! It was you and your Scottish Tunes that, at last, brought me to pick up my ukulele about 40 years after It was given to me when I was a child. Now I have one question about Ka Ipo Lei Manu which John King is playing here: I managed to write down the music and also to play it ok, but I cannot see what he is doing to play this high f-g-f trill in the third phrase (at about minute 1.27 and later on several times). Do I have to play the three notes separately (which I would never be able to in this speed …), or is it one of those pull-off and hammer-on effects that you describe in your “sounds irish” tutorial? Your help would be very welcome – as a violin player, I am sort of fast with my left hand, but not so with the right hand, so I desperately need a hint …;-)

Thank you so much and greetings from Germany, Mechtild

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Mechtild, actually some of the ornaments are across the strings and others are a hammer-on pull-off all in one (only the first note is plucked). I have John King’s arrangement which I downloaded from his website. It might help to clarify things. This is the link: http://www.nalu-music.com/nalu/Ka%20Ipo%20Lei%20Manu.pdf

LikeLike

Hi Samantha, thank you very much for your answer, this helped a lot! And also for the arrangement itself – I managed to download the pdf, but unfortunately, the website nalu-music itself seems to be out of order now. I had visited it before (also for downloading the blank music sheets for tab), but now there is always a database error occuring …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, there seems to be a problem with the website. I’ll try and find out more.

LikeLike